ALL THE LIVES WE DO NOT SAVE: The Hidden Cost of Low Voluntary Blood Donation

“Hello,” he said, “this is the father of the boy you helped get blood donors for yesterday. I just wanted to say thank you for helping us. Two of the contacts you shared came by to donate blood. And although we still need several more pints for his treatment, I just wanted to thank you for taking the time. May God send helpers to you in your time of need.”

That was the call.

I was deep into my work at the microbiology lab when it came in, and you know what?

I ignored it at first.

I had plates to streak, samples lined up inside the biosafety cabinet, and three hours of soul-wrenching, body-aching drudgery ahead of me.

But then he called again.

And this time, I exhaled, stepped away from the bench, and picked up, almost ready to snap at the unknown caller. Little did I know that the call I was about to answer would inspire me for the rest of the week and serve as the sounding gong to starting BloodLines.

His name was Mr Ogunbowale. His son was newly diagnosed with leukaemia.

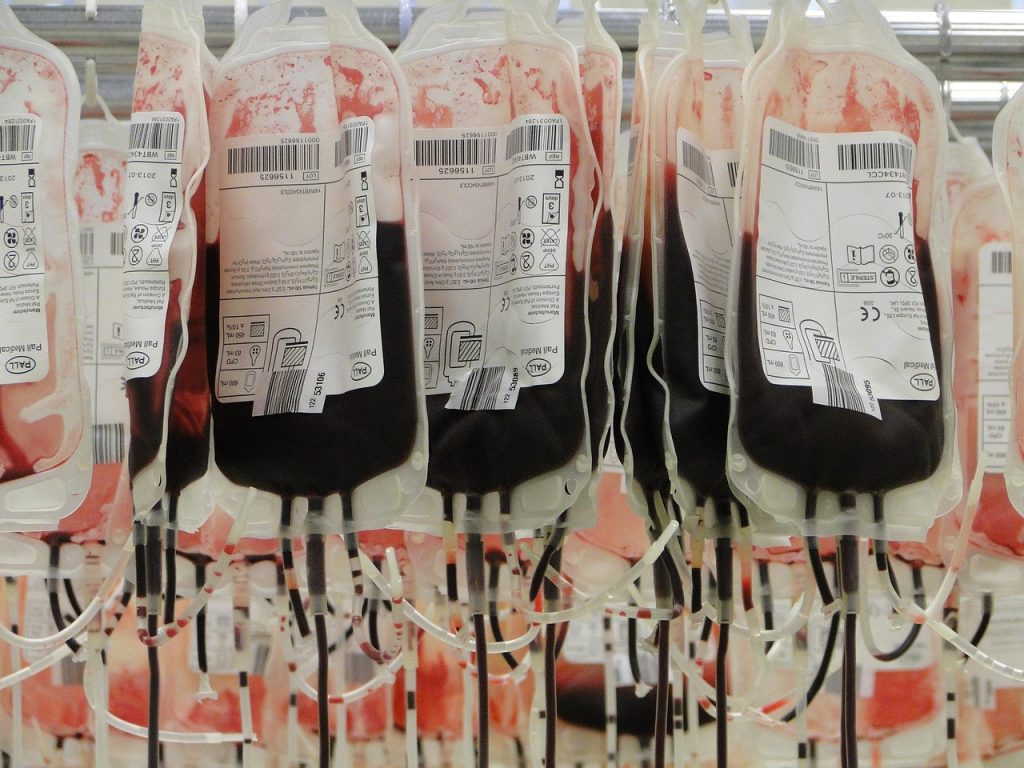

He, his wife, and their extended family had been scrambling from pillar to post, trying to gather blood for a long, exhausting course of cancer therapy. Two units of blood were just the beginning — Leukaemia patients can use up to 50 units in a single treatment cycle lasting weeks to months. And they were still searching for more donors, still making calls, still begging.

But leukaemia patients are not the only ones who need blood.

Accident victims.

Mothers with post-delivery complications.

Patients undergoing surgery.

People with chronic illnesses.

The list is endless.

Everyone needs blood.

In Nigeria, about 2 million units of blood are needed annually. That’s about 5,000 units needed every day.

Now here’s where the heart drops — only about 500,000 units are collected yearly.

That leaves a shortfall of 1.5 million units.

Meaning 3 out of every 4 people who need blood won’t get it.

Meaning for every four lives we could save, three would have to die.

But it gets worse.

Of the 500,000 units collected, only about 50,000 come from voluntary, unpaid donors. And voluntary donors provide the safest blood. Not “safe enough.” The safest.

Why does that matter?

It’s one thing to get blood, and another thing entirely to get safe blood. People die from transfusion reactions caused by unsafe blood every day.

So, run the numbers again:

If 2 million units are needed this year, and only 50,000 units from voluntary donors are reliably safe…

That’s 2.5%. So for every four lives we could save, saving one is even a gamble.

Shocking? Laughable? Heartbreaking? Take your pick, but that’s our reality.

People die every day, not because we lack the knowledge, tools, or technology, but simply because you and I have refused (or are not encouraged) to give them blood.

Two hundred years ago it wouldn’t have mattered, but since Dr James Blundell performed the first human-to-human transfusion, we’ve mastered the art and science of blood donation and transfusion. We know how to collect blood safely. We know how to screen it. We know how to store it. We know how to transfuse it.

Yet people still die. Even though we promised ourselves in 2015 that no one would have to die under conditions we know how to manage (think SDG 3). Because the blood they so desperately need is not rare and is not hard to find. It is in us. And there are millions of us.

We cannot manufacture blood (no, not even the blood banks). We cannot get it over the counter either. The human body remains the only source. So if blood doesn’t come from you and me, no one’s gonna get it.

Moreso, the notion that blood will be available when anyone needs it is absolutely false. The prospect of ‘biological eternity’ for blood, even at -196°C, does not exist either. If anything at all, blood gets expired. After 35 days, whatever blood is banked in the blood bank becomes harmful and unfit for use.

And despite the development of plasma substitutes and other products, technological progress in freezing and preservation of blood to permit longer-term stockpiling, and the possibility of separating blood components for broader and more extended use, there is still no substitute for the more significant percentage of patients who require direct use of fresh whole human blood.

So it means we must donate regularly if we want people — including ourselves — to live longer.

Now here’s the ultimate irony:

Donating blood doesn’t cost us much.

It takes just a pause, a pinch, and a pint.

A pause from our schedule — the length of a lunch break. A pinch from a needle — no worse than a paper cut. And one pint out of the nine pints in your body at any moment.

Yes. You have 9 pints of blood flowing in you at every given time, and just 1 out of 9 is what is required.

Plus, they never take what we can’t spare. Before every donation, your blood volume is checked to ensure you have more than enough for yourself and an excess to give. If you don’t have surplus, you won’t even be allowed to donate. And when you do donate, your body replenishes what you give in a few days.

So again, what’s stopping us?

Shall we keep hoarding what could save someone’s life?

Shall we keep letting millions die when we know the solution?

Or shall we take that one small step to the clinic and book a regular appointment — to save all the lives we can?

Because just when I thought the story had ended, another call came in.

“Hello,” he said. “It’s me again, the father of the boy you helped to get blood. Please… the doctors said we’re going to need another two pints. Can you help us?”